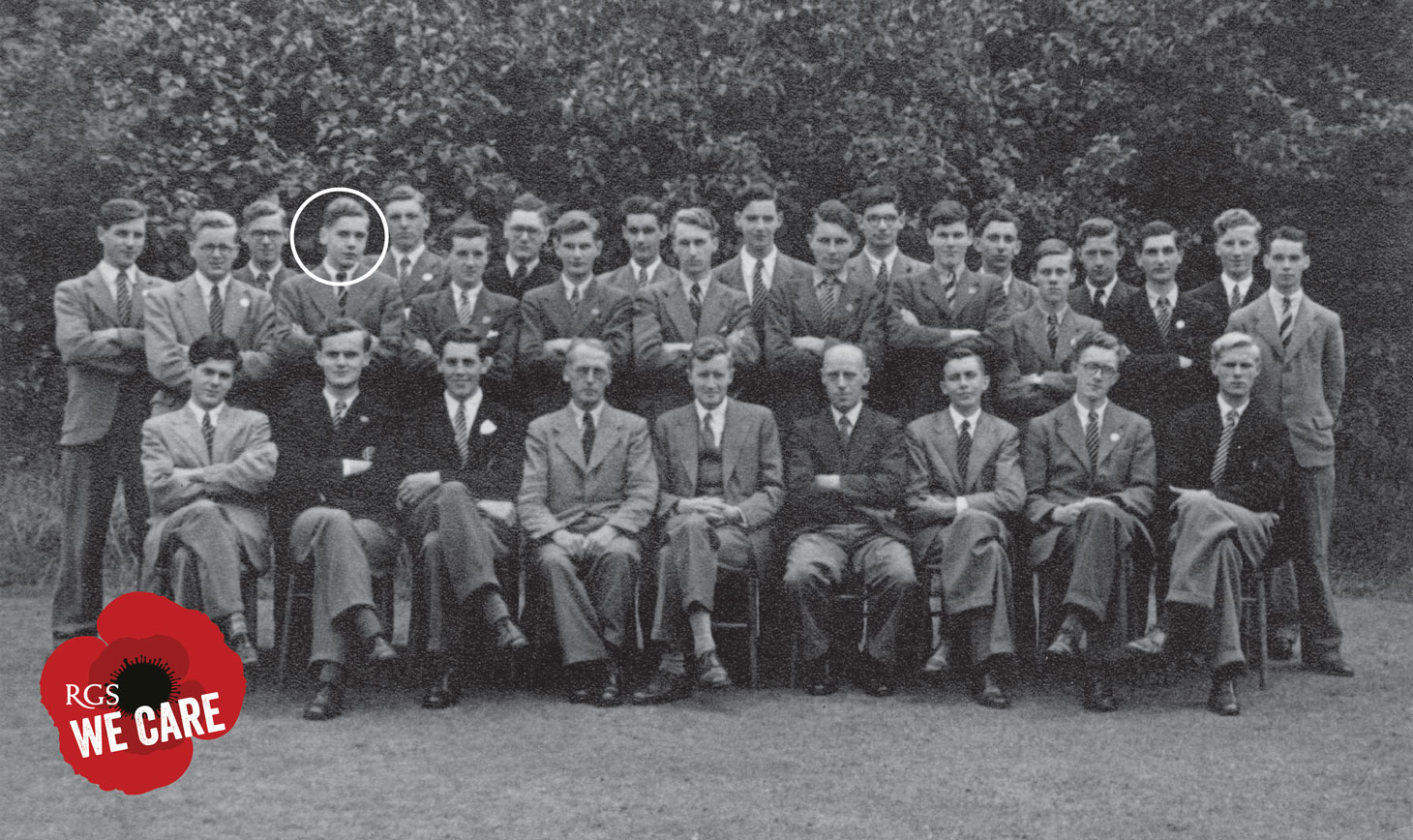

Recollections of RGS in WWII

“Somehow my older brother and I did not get evacuated during the war, so I began Reigate Grammar School in the first form at the age of ten in 1942 (having an October birthday). Many of the staff, who could be called up for the forces, had already gone. Boke was the Headmaster and Mr W Sweatman was my form master. Having been confirmed as a waste of space at my little prep school, I was astounded to discover that I did know a few things, and the first years were like falling off a bus. Other members of staff were Mrs Goodchild, Miss Haagens (known to all as Blondie) and Dr HV de Montgomery who had continental notions of class discipline.

Air raids, given our proximity to London, a major target, and being under the flight path from occupied France or Germany, were a constant interruption to the school day. Air raid shelters were dug all around the edges of the playground as it was then. They were long and narrow, and we sat opposite each other along the duckboards on the passageway between the rows of slatted seats. The duckboards were essential, as the shelters were very wet, and patchily dark. How the teachers coped with two rows of their class mixed up with several others disappearing into the haze in the distance I’ve no idea. I do recall I especially hated geometry in the shelters, as the point of a compass stuck through the thin paper we had to use, and straight into your leg!

And then the doodlebugs started to be a regular part of every day life. The big 500 bomber raids were mostly after dark: I can still hear in my mind the noise such a group of four-engined planes made. But they were preceded by a siren, and followed by an all clear. Doodlebugs were individual robotic flying bombs with a jet engine and were rarely preceded by a warning.

I do recall standing in the playground one day with Mrs Goodchild as the rest of the class had already gone into the shelter, and she asked if I knew anything about these devices, as one was flying overhead while we spoke. I pointed to it, and said, ‘As long as the engine sounds like that, there is no need to worry. It is only when it suddenly goes silent that you need to take cover.’ When the V2s began, there was no time to do anything. The first you knew of them was a flash, and then, later, the bang.

At home, we spent the first years of the raids sleeping in the cellar; on a flat deckchair held off the floor by a couple of orange boxes. We had no electricity in the house at all then, just gaslights and candles. Torches were not a lot of help, as number eight batteries were as rare as peers who get to the House of Lords on merit. But as the war went on we got more and more blasé about it, and moved up one floor to sleep on the floor against the wall behind the sofa, and then, for the first time in the first few months of 1945 back into the bedrooms that we’d nearly forgotten about. I recall the words of comfort our old next-door neighbour gave to his dog (who barked vigorously at each and every explosion): ‘Don’t worry, Bobby, it’s only a bomb.’

At the bottom of the tiny garden was the Redhill Sports ground, in the middle of which was a searchlight, a large machine gun, a barrage balloon and a listening device to find the position of the attacking craft. I vividly remember one day watching a couple of local teams playing cricket in the centre as a doodlebug rattled into view. They went too quickly for the RAF to catch up with them, but the gunners in the field always liked to try, though they never hit one as far as I know. The cricketers calmly lay down on the grass until the gunner stopped trying, and then the umpire stood up, and called ‘Over’ and the game continued. But the two quoits pitches were turned into a show-allotment, to encourage us all to Dig for Victory.

School meant twelve miles of cycling every day, come hail, snow, wind or rain. My only accident was to cycle into the back of a bren-gun carrier that had suddenly stopped in front of me. Stop lights they did not have. There were practically no streetlights, of course. You could see the stars in those days. Cricket gave way at the end of 1944 to baseball, as we were over-run with Canadians, in preparation for D-Day. Almost every home, including ours, had one or two billeted on them, and they were great men, exotic, with real food to eat. Sometimes we got a steel can of dried egg as a gift, and very welcome it was, too. I find that those who were born after the war find it hard to believe that by 1944, German PoWs were allowed considerable freedom of movement: they had to wear clothes with patches on, but otherwise could largely come and go as they pleased. They would sit in the parks, walk in the streets, come to the youth club and beat us at table tennis or billiards.”

John Ticehurst (RGS 1942-1950)

Related articles

Germany 1945: letter to the Headmaster

Remembering those lost in WWII

VE Day celebrations: a day off school!

1939-1945: a potted history of RGS